…and anyway, what is a national labour market, once you start thinking about it?

— Bridget Anderson, Who is a migrant?, “Who Do We Think We Are?” Podcast

Author: Marco Rocca

In our recent article, Audrey Deverson and I explore the legal meaning of the concepts of “temporariness” and “labour market” in the context of the EU framework for temporary labour migration. This is part of our work on the E-BoP project and was aimed at “operationalising” these concepts to prepare the further steps of our research. Here, I want to zoom-in on a specific part of that research, that is, our work on the use of the concept of “labour market” in EU law.

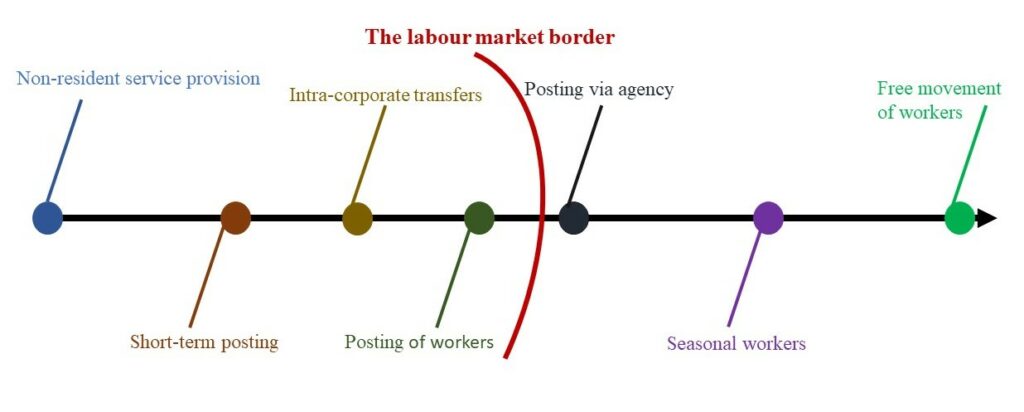

I was drawn to analysing this concept by the fascinating situation where the three forms of temporary labour migration covered by E-BoP are explicitly placed in three different positions with respect to the labour market. With three points on a map, I thought, it should be possible to draw a “border” of the labour market:

- Posted workers do not at any time gain access to the labour market of the host Member State (as stated by the Court of Justice in the Rush Portuguesa case)

- Intracorporate transfers are not likely likely to affect the labour market of the host Member State, as they do not substitute any national or EU (Impact assessment of the Intracorporate Transfers Directive

- Seasonal workers form a part of the national labour market where they work (Impact assessment of the Seasonal Workers Directive)

This led me to wonder which definition of labour market was (implicitly) at play here. The issue being one of determining the conceptual scope of this expression, as this is not a legal concept nor is explicitly defined by a legal document, together with Audrey we set out to design a way to explore this concept. Notably we wanted to avoid working on the basis of a few supposedly “seminal” documents (e.g. a handful of important decision of the CJEU), cherry-picking our way to a nice consistent definition. Instead, we decided to analyse every mention of “labour market” in EU “hard law” documents, defined as those having a binding character, leading to a corpus of 1803 paragraphs of text.

To code those we identified 5 definitions of “labour market”. In very short these are

- TEXTBOOK: the labour market is a market, where supply and demand meet leading to the setting of a price

- SOCIOLOGICAL: the labour market is a set of institutions governing the exchange of labour

- INTERNAL: the labour market is the way in which any given company internally sets the price of labour

- SPATIAL: the labour market is the area (geographical or industrial) within which workers can move more or less freely between one job to the other

- STATISTICAL: the labour market is the numerical representation of composed by employed/unemployed people in a given area or profession

We coded each paragraph separately, only putting our data together at the end of the coding. We also had a protocol in place to handle disagreements (which, as you will see in a moment, were frequent). This was based on a confidence score that we gave to our coding of each item (0 for “not confident” and 1 for “confident”), where “confident” coding would prevail over “not confident”, and disagreements backed by the same level of confidence would lead to an item being coded as UNDECIDED.

If you want to dive deeper into our Corpus and see how much you agree/disagree with our coding, you can find it, together with our Codebook, here. For a funny anecdote, when we submitted it, we had to go through a somewhat philosophical exchange with the people in charge of the repository, as they had to determine whether this was “Social Sciences” or “Humanities” (in the end, the former prevailed).

These were our final results:

| Labour Market Definition | Total |

| TEXTBOOK | 359 |

| SOCIOLOGICAL | 100 |

| INTERNAL | 2 |

| SPATIAL | 175 |

| STATISTICAL | 110 |

| UNDECIDED | 538 |

Looking at the table, the first thing that stands out is the vast number of UNDECIDED items. As a reminder, these are items which we separately placed in different categories and with the same amount of confidence. The fact that more than a third of our items ended up as UNDECIDED in way confirms the relevance of trying to open up the conceptual black-box. While EU law and legal actors use in multiple occasions the expression “labour market”, trained legal researchers themselves have a hard time agreeing on its meaning.

For the rest, the main result of our coding is the predominance of the TEXTBOOK items. This can be partly explained by the specific competences of the EU in social and economic policies. At the same time, it seems safe to argue that its strong prevalence makes it a good starting point when trying to assess the actual meaning of the expression “labour market”, when used by EU legal actors. Indeed, the TEXTBOOK definition is the most used one across four out of five of the institutional actors adopting the texts covered by our Corpus. At the same time, it is also worth considering a SPATIAL meaning when it comes to migration, as this was the prevalent definitions in the subjects of Extra-EU migration and Intra-EU migration.

As mentioned in the opening, this is part of a broader research, so that these results will feed into the further steps of E-BoP. However, the concept of “labour market” is also relevant in other areas of the law (such as social security or migration law), so we hope that our results might be of interest to other researchers. Beyond the contents, this represents the first (therefore, perfectible) application of our protocol for systematic document analysis. In designing it we drew inspiration from existing empirical legal research, systematic reviews performed (among others) in medical research, as well as the coding of qualitative materials in social sciences. We believe it to be a valuable tool to explore the conceptual scope of under-defined terms and expression used in legal documents.

For the long version, see Rocca, M., & Deverson, A. (2024). Time and Labour Markets in the Regulation of Temporary Labour Migration in the European Union. Italian Labour Law E-Journal, 17(1), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1561-8048/19338